Dimensional Signs

Wood You?

Many signmakers still work with the old-school substrate.

Published

18 years agoon

For centuries, perhaps even millennia, myriad woods — redwood, oak and cedar, among others — have served as signage substrates. A wooden sign gave a shop or other enterprise an authentic air, and its workability pleased the signmaker.

Today, synthetics, such as high-density urethane (HDU), and alternative substrates, such as PVC and composite materials, have, to an extent, eclipsed wood.

However, wood boasts its own attributes. Wood has its own grain, making grain frames unnecessary; its higher density makes it more resistant to breakage than HDU, and it’s not abrasive to the touch. Besides, many would-be customers prefer the genuine article.

Learn what five signmakers and a wood-blank manufacturer have to say about the intricacies of working with wood.

Joe’s experience

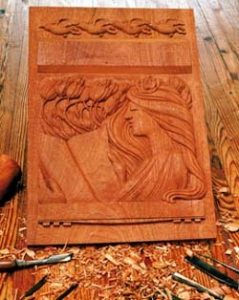

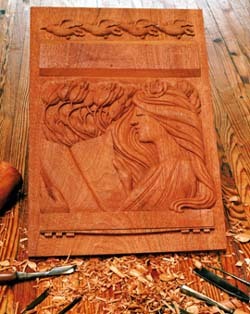

Joe Cieslowski, owner of Connecticut Woodcarvers Gallery (East Canaan, CT), began carving at age nine as a Boy Scout. At 14, he was teaching carving techniques and selling his work. He opened his own shop in 1977. According to Cieslowski, approximately 80% of his work involves carved pictorials. He teaches such skills as relief carving and crafting raised, prismatic letters.

Given his teaching background, Cieslowski espouses studying wood’s properties — for that matter, any material — prior to fabrication. He notes that most people’s woodworking techniques are based upon cabinetmaking, where weatherproofing isn’t a concern.

This is what enabled HDU to grab a foothold in the market,” Cieslowski said. “Many people didn’t know how to make wooden blanks for outside use. It goes back to understanding how a substrate will react in an outdoor environment.”

He prefers crafting signs with Eastern white pine, because it’s readily available in his region, offers a better grain pattern and has less porous fibers than sugar pines, making it more compatible with transparent stains that amplify the wood’s grain.

Having encountered problems when others have supplied blanks for a sign, he now fabricates his own, using standard woodworking tools, including a table saw, band saw, jigsaw and various types of sanders. To glue the panels together, he uses Franklin Intl.’s (Columbus, OH) TiteBond II water-resistant, wood glue.

“Anyone who tries to use dowels or biscuits to join pieces together for strength is wasting his time,” Cieslowski said. “They can help align the boards, but there’s nothing else you can do to strengthen the glue joint.”

Rather than using a typical stain, he begins treating wood with 1Shot® enamel. Cieslowski points out that it contains the same ingredients as a stain: pigment, vehicle and drier. To make 1Shot perform similarly to stain, he adds 30% to 40% reducer.

After staining the wood, he applies four coats of Minwax® spar polyurethane. Cieslowski notes that spar polyurethane is readily available to the public and helps the customer to refinish the sign every few years as necessary.

Cieslowski maintains a relatively low-tech operation; his tools of choice include gouges, knives and, to a lesser extent, chisels. He advises “carving like a coward” — in other words, be cautious, and don’t remove more material than feels comfortable.

“Keep your tools sharp,” Cieslowski added. “Not only do sharp tools work more effectively than dull ones, but you’re less likely to hurt yourself.”

Cieslowski prefers working with wood over HDU because of its strength and workability.

“It comes down to pay me now or pay me later,” he said. “Using HDU, you’ll typically spend more initially on the material. HDU won’t warp as easily and does offer some stability. But, to make [HDU] strong enough, you need to use epoxies and special primers to handle wind load and other outdoor factors. HDU is a good product, but, in my opinion, this time and expense can be better spent becoming more familiar with wood.”

He’ll typically apply two coats of 1Shot enamel atop two coats of Sign Arts Products’ SignPrime™. When Cieslowski gilds a sign, he mostly uses quick size.

“With size, it’s all about the timing,” he explains. “I always use a stopwatch, and my target time is an hour and a half. If the the window closes in that time, I just resize and set my watch for an hour and 15 minutes.”

Heartland techniques

Mike Hoy, co-owner and general manager of Columbus Sign Co. (Columbus, OH), is a third-generation signmaker. His grandfather, Art, founded the shop in 1920, turned the business over to his son, Bill Sr., who subsequently turned it over to Mike and Bill Jr.

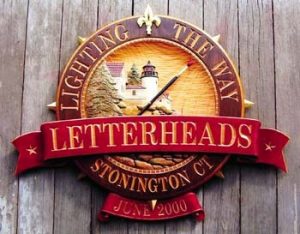

Using the company’s Gerber Scientific Products (South Windsor, CT) Sabre 408 router and companion AutoCarve™ software, the company combines such routing techniques as crafting incised, prismatic letters and V-grooved edges. To achieve V-grooving, the software calculates a path for the router to create reverse-prismatic shapes and letters upon a flat surface.

Hoy likes a router’s ability to create interlocking, “male” and “female” parts. He’s grateful for technological advances that have made crafting signs more efficient.

When fabricating wood with a CNC router, Hoy advises monitoring the machine’s speed as the bit moves perpendicularly along the substrate. The CNC router operator must be cautious to prevent splintering, particularly amid incised letters.

The company primarily uses redwood, cedar and pine, though he laments the markedly diminished pool of quality redwood. While he praises HDU for its ease of use, he cites that once it’s painted or stained, it loses its grain.

For signs smaller than 5 ft. wide, they’ve constructed an indoor blast facility, including a dust-collection system. For larger signs, they’ll take it outside on a weekend, when their silica sand abrasive won’t affect the shop’s neighbors.

For decoration, Hoy prefers bulletin enamels’ vivid colors. For indoor signs, he’ll use lacquer stains; outdoors, he likes polyurethanes’ high durability.

Webb’s wood work

Wayne Webb, owner of Webb Signs (Pensacola, FL), began making wood signs as a second job in 1985 after having read Patrick Spielman’s book, Making Wood Signs.

Webb commonly has problems finding quality wood with vertical grain, which typically indicates stronger, more easily manipulated wood. Redwood’s density and rigidity make it particularly well suited to vertical signs that span 10 ft. or more.

To fabricate wood signs, Webb tries to work an entire sign from a single piece, which simplifies creating uniform density, grain and moisture content. He’ll run the piece through a saw blade set at 90°. If the boards aren’t completely 90° vertical grain, he’ll alternate the boards’ direction to balance them. This prevents warping later.

After arranging the boards, he creates joints with his table saw. Webb runs each piece through the 90° saw blade and shaves off enough to create an edge. After running each board through in the same direction, he lays them in order. After joining one side, he flips every board except the first and last and runs the other joint.

After setting the boards and brushing out dust with an air hose and brush, he bonds the panels together with epoxy and clamps. The clamp applies just enough pressure to squeeze glue from the joint. After a night of curing, Webb levels the surface with a 50-grit belt sander, moving diagonally with the grain to flatten the boards together. Next, he’ll sand with an 80- or 120-grit belt to smooth the surface.

After dusting, he begins with a single coat of solvent-based primer thinned with toluene or xylene, which he sprays onto the surface. After letting it dry for two days, Webb sands with 150- or 220-grit sandpaper, then sprays on two or three thin coats of acrylic, direct-to-metal (DTM) paint. Because of trapped moisture, this mixture requires approximately five days to dry.

He typically sandblasts his signs. He cuts Anchor 153 medium-tack stencil using his Ioline (Woodinville, WA) plotter, then uses silica at approximately 100 psi. He uses a homemade filter to extract the rocks from sand, which prevents dents and yields finer grain from the blast. The stain seals tannins within the first coat for crisp, flat finish.

In Dixie

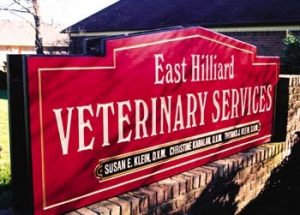

Donald Thompson, owner of #1 Sign Designs (Laurens, SC), operates a four-year-old, 6,000-sq.-ft. shop, where he primarily sandblasts wood signs. HDU is an option for his customers, but Thompson says they tend to prefer wood.

“If you hold panels of wood and HDU side-by-side, naturally, the wood is going to be denser and feel more substantial,” he explained. “I think my clients tend to choose wood primarily for that reason.”

Thompson sandblasts signs using cedar and cypress, though he prefers cedar because cypress is more dense and less practical. He fabricates signs using 5-in. lengths of doweling rod and a jig, and bonds the pieces using Elmer’s Wood Glue.

Thompson particularly admires cedar because its color and grain naturally darken and beautify with age. However, most customers want their sandblasted signs painted.

Thompson prefers to “overdo” the coating; he says it’s better to err on the side of caution. He decorates every sign with three coats apiece of polyurethane primer and acrylic-latex paint. Thompson believes a cedar sign should last 10 years outdoors if it’s refurbished.

Signs up North

Josh Halprin, owner of CanSign (Canmore, Alberta, Canada), first encountered the sign business while screenprinting shirts in college during the late ’60s. He first opened his own shop in 1979, operated it for a decade and pursued other opportunities before re-opening in 1993.

Halprin has tried cedar, fir, mahogany and pine. Further, he’s quite particular with his wood. It must be “clear” — free of knots, dents, etc. — and contain less than 8% moisture content. Such wood must typically have aged in a low-moisture environment for at least two years.

Halprin notes that lamination impacts a board’s quality. There are two methods: face-grain, or laminating flat pieces together, and edge grain, cutting pieces in half and turning them sideways. Edge-grain constructions are more time-consuming, they’re more stable because they comprise smaller pieces, Halprin said. Alternating the grain’s direction helps create balanced structure.

CanSign projects begin with the shop’s Gerber Sabre router, which creates a rough form of the final design. A sign that would require an hour takes only 20 minutes after the roughing-in process.

Halprin emphasizes keeping sharp bits when routing, which usually involves changing bits with every job. Although carbide bits work well, he particularly admires cobalt bits, which he said create crisper incisions, and better expel wood chips, Halprin said.

He maintains a full complement of hand tools — rasps, chisels, gouges — but frequently uses his Dremel® tool because it produces fine detail. However, he cautions that artistic skill and tool experience are necessary before attempting to use a Dremel.

For an ideal finish, a wooden signboard must have rounded edges. According to Halprin, a sign with a square, 90° edge is “virtually assured” of paint failure. Before decorating a sign, he scuffs the sign’s edges with a sanding block. He’ll apply as many as seven coats.

“In Canada, we have rough winters,” Halprin said. “It’s a simple fact that a sign will need to be recoated within seven years.”

Manufacturing wood blanks

AllWood Sign Blanks (Errington, British Columbia, Canada) began manufacturing wooden sign blanks approximately 12 years ago. The management of Center Island Cedar Products Inc., AllWood’s parent company, perceived an opportunity to market cedar blanks to the sign market.

According to Andy Miller, AllWood’s sales and marketing manager, Western red cedar exhibits the same grain quality as redwood, the longtime signature wood of the sign industry whose supply has dwindled.

“Western red cedar has short grain, which makes it very workable; it can be carved, routed or sandblasted,” Miller explained. “It doesn’t attract bugs because of its high level of natural oils.”

The company purchases raw planks — typically 4- or 6-in.-thick boards — and cures them in its kilns, which are set at roughly 160°F, for two weeks. After the boards have cured, AllWood affixes the pieces together using a two-stage, epoxy resin, and runs them through a radio-frequency glue press.

The press emits electrical impulses, in the form of radio waves. Gluing equipment transmits radio waves in confined patterns within the machine, generating heat that bonds a single blank. After the blank exits the press, AllWood uses a 52-in. planer/sander to create uniform smoothness.

Cees Van Santen, AllWood’s office manager, said that AllWood avoids incorporating biscuits or dowels when fabricating blanks because, when sandblasted, they often reveal a piece that can’t be blasted and effectively ruins a job.

The company manufactures more than 90% of its blanks at a 13/4-in., standard depth. Thinner blanks may be appropriate for indoor applications, such as wall plaques, whereas two-sided signs may require a thicker substrate.

When storing the blanks, Miller suggests laying them flat and above the floor to prevent cracks. Further, storage within a dry room with low humidity essentially prevents warpage.

AllWood suggests using an oil-based primer to prevent tannins bleeding through the woods once it’s painted.

| Companies Mentioned |

#1 Sign Designs Inc. AllWood Sign Blanks Ltd. CanSign Columbus Sign Co. Connecticut Woodcarvers Gallery Webb Signs |

SPONSORED VIDEO

Introducing the Sign Industry Podcast

The Sign Industry Podcast is a platform for every sign person out there — from the old-timers who bent neon and hand-lettered boats to those venturing into new technologies — we want to get their stories out for everyone to hear. Come join us and listen to stories, learn tricks or techniques, and get insights of what’s to come. We are the world’s second oldest profession. The folks who started the world’s oldest profession needed a sign.

You may like

ISA Enters Strategic Partnership with The Wrap Institute

Summa Releases GoProduce Flatbed Edition 3.0

Preserving the Past with The San Jose Sign Project – Part 1

Subscribe

Bulletins

Get the most important news and business ideas from Signs of the Times magazine's news bulletin.

Most Popular

-

Business Management1 week ago

Business Management1 week agoWhen Should Sign Companies Hire Salespeople or Fire Customers?

-

Women in Signs1 week ago

Women in Signs1 week ago2024 Women in Signs Award Winners Excel in Diverse Roles

-

True Tales2 weeks ago

True Tales2 weeks agoSign Company Asked to Train Outside Installers

-

Editor's Note5 days ago

Editor's Note5 days agoWhy We Still Need the Women in Signs Award

-

Maggie Harlow2 weeks ago

Maggie Harlow2 weeks agoThe Surprising Value Complaints Bring to Your Sign Company

-

Line Time1 week ago

Line Time1 week agoOne Less Thing to Do for Sign Customers

-

Product Buying + Technology7 days ago

Product Buying + Technology7 days agoADA Signs and More Uses for Engraving Machines

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoMUTOH Partners With Wasatch for RIP Software Package