Design

When Irish Eyes Are Smiling…

A look at several signmakers and muralists from the Emerald Isle

Published

18 years agoon

Everyone’s Irish on March 17. It’s not uncommon to see people named Lombardo, Kowalsky or Chang (or Aust, for that matter) dance a jig, quaff pints of Guinness or listen to Gaelic Storm on that particular date.

However, for those fortunate enough to hail from Ireland, these aren’t merely the commemorations of the day their patron saint drove the serpents from the nation. They’re manifestations of a nation whose history and heritage far outdistance the United States — a nation that seemingly imbues its subjects with a deeply held pride and passion for life.

The following troika of Irish signwriters” — as such professionals are called on that side of the Atlantic — conveys these attributes in their work.

Bringing Eire to the States

It would be tragic to deprive the United States of talented artisans that reside within the Shamrock Republic. As such, painter, muralist and Gort School of Art instructor Fran McCann was summoned to paint murals for Claddagh, an authentic, Irish-style pub under construction at Newport on the Levee, an upscale shopping center in Newport, KY.

As of mid-January, McCann had painted two murals, with as many as six slated for completion before his early February return to Gort, Galway County. One of the murals depicts Claddagh — a coastal town originally settled by the Vikings but torn down in the early 20th century due to the spread of tuberculosis — in the mid-19th century. The artwork features several boats (called hookers), teams of workhorses and (natch) Guinness barrels.

McCann painted the 10 x 24-ft., plywood mural with exterior-grade latex paints, mixed with acrylics to obtain enhanced tones, plus some enamels and high-gloss paints. Latex paints aren’t available in Ireland, he notes, but he was happy to have them at his disposal.

“High-gloss paints are the worst paints in the world with which to paint murals, but that’s what we have back in Ireland,” McCann explains. “When I got here, that’s what I was expecting. When I began working with latex paints, I liked them very much.”

He primarily used 1-in., medium-width brushes, though he also incorporated 1/8-in. signwriter’s and other brushes, 4-in. foam rollers and painting knives. Finally, two coats of water-based, matte-finish varnish brought added warmth to the colors.

At press time, the mural was scheduled to be separated into six, 10 x 4-ft. sections, hinged for installation at the pub’s entrance, and situated into a 6-in.-thick wood frame.

McCann’s other completed mural is a 4 x 8-ft. piece that commemorates Connemara’s Kylemore Abbey, the home of a Benedictine order of nuns that is one of the region’s prime tourist attractions. This mural required similar paints as the Claddagh depiction, with 1-in. brushes used throughout.

He’s very aware of the seemingly mystical aura that surrounds Ireland, though he can’t quite pinpoint its origin.

“It’s difficult to explain, really,” McCann says. “My country is a very unique place, and we regard some places as almost mystical. There’s something about the rolling green hills and valleys that just seems to stir passions in the whole lot of us.”

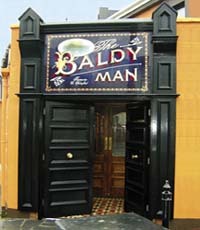

A shine on Old Baldy

The proprietor of E. Quigley & Co. and a resident of Kilkenny City, Ireland, Eoin Quigley fabricates gilded signs from wood, glass, stainless steel and PVC. He also handpaints murals.

Jim Quinn, architect of The Baldy Man, a pub nestled within The Sands Hotel & Resort Complex in Tramore, Waterford County, called upon Quigley to create murals and ceiling graphics for his business’s interior. This project spanned six weeks, during which time Quigley and Baldy Man owner Freddie Piper discussed fabricating new, exterior signage for the tavern.

After convincing Piper and Claddah Interiors — the company that handled the pub’s inside designs — that the exterior’s appearance should match the pub’s confines, Quigley embarked on creating a carved and gilded glass sign.

Adapting the lettering from an antique, gilded beer sign that Piper owned, Quigley spent three days formulating his design. Basing his style upon traditional, Victorian transom pub signs, he used lettering techniques borrowed from his signwriting grandfather. While incorporating glass chipping and gilding into the design, he wanted to blend in a pictorial element, as well as intricate decorations around the sign’s perimeter.

“I knew from the beginning that the sign needed to be carved,” Quigley says. “This would make the sign appear more dimensional. I knew there would be considerable expense involved, but I had the good fortune of working with a client who gave me creative carte blanche and never interfered with my process.”

Initially, Quigley sent an .EPS file of the 4 x 6-ft. sign to Mark Dowling’s Carlow Graphics (also of Kilkenny City), which carved the areas within the “Baldy” lettering with their Sabre router.

This allowed him to proceed with the rest of the sign — the diamond designs around the border, the oval surrounding the pictorial and the lower portion of the letters. He sandblasted these areas and then applied chipping glue. As the glue dried, it chipped the glass surface, leaving embossed, leaf-like shapes within the letters.

Following this application, Quigley applied a mica-hydrofluoric acid paste, which left an etched stipple on the grapes and remaining text.

Working on a job too large for screenprinting, Quigley next applied Oracal paint masking and began to coat the glass. To ensure accurate registration, he shined a light through the back of the glass, a step that took an entire day. This was especially vital for reviewing the chipped and etched areas, he said.

For the background, he created a circular blend, shading the color from a brilliant blue in the center to an almost-black navy towards the outer edges. Before the paint became tacky, he lifted the mask, allowing the edges to be gilded a chance to fan out.

Quigley water-gilded 23K goldleaf onto the diamond borders, ovals and main copy. Next, he applied silverleaf to “Tramore, Co. Waterford,” and oil-gilded the scrolls with 12K leaf using 1Shot® fast-size, which was then spun. For added effect, he scratched out the area on the scroll and shaded under the “T” and “B” in “The Baldy.” Because he wasn’t screenprinting, he reverse-handpainted the carved letter openings, oval and diamonds.

At this point, Dowling returned Quigley’s carved panel, which had taken four coats of primer, with sanding in between applications. Quigley then finished the panel with 23K leaf.

To complete the glass, Quigley applied a Gerber EDGE™ print of a mural he’d created for the tavern’s interior, depicting the region’s sand dunes — affectionately known locally as “the baldy man.” He also accentuated the remaining border with blue jewels and copper flitters.

After installing the sign with the assistance of Claddagh Interior Manager Robbie Moorehouse, Quigley called the job complete, with a paycheck that carried added significance.

“It’s the first check I’d ever received paid in Euros,” Quigley recalls.

Creating an identity

James Marshall, proprietor of Poulnabrone Signs & Design in Connemara, Galway County, began his signmaking career, studying graphic arts at college in London. He had a rather unusual client for his first “real” job out of school.

The Emir of Kuwait wanted all the relief cornicing and panels gilded at his palatial London residence. The job took Marshall and four others a week to complete, and they spent $12,600 on 22K goldleaf adorning the walls of the Emir’s living room and bedroom.

One of the primary inspirations for Marshall’s career is Mike Stevens’ Mastering Layout, which he continues to consult.

After working for seven years in various shops, Marshall moved to Galway in 1999 and opened his own shop. His repertoire includes storefront signage, window and vehicle graphics, banners and pub signage, the center of social life in the Republic of Eire. He’s especially passionate about creating banners that stand out amidst the crowd.

“Ninety-nine percent of the banners here are single-color vinyl,” explains Marshall, who uses Deka water-based enamels to decorate banners. “It’s hard to tell any of them apart. I want to create banners that are going to be memorable. And, as a matter of principle, I refuse to produce any graphics using Times Roman or Helvetica fonts.”

Marshall faces fierce competition in Galway County from five other commercial signshops. He also encounters challenges due to limited product availability — 1Shot enamels aren’t available in Ireland, and he has to order |2438|® film from the United States. However, he believes the Irish passion for traditional crafts, including signage, keeps him in business

One of Marshall’s favorite jobs was fabricating a new sign for Galway’s Huntsman Inn. The tavern’s old sign and its frame had begun to deteriorate. To construct the sign, he used 1/2-in.-thick, marine-grade plywood — standard plywood wouldn’t last in coastal conditions. Given its shoddy state, Marshall sanded back the signframe, then repainted it with Metalguard primer, which has an alkaloid rust-inhibitor.

He gilded the text with 22K goldleaf, and painted and airbrushed the central graphic. After priming the double-sided sign until it was suitable for a high-gloss finish, he spent three days gilding and painting, then a morning to frame it.

Marshall also provided a new look for Newcastle’s G&L store. The shop had already applied a coat of aluminum-colored wood primer, which Marshall followed with a gray basecoat and two coats of high-gloss dark blue. Next, he applied 1Shot reflex green, process blue and process green pearlescent enamels with a sponge. Marshall says, “These paints catch the light very well and create interesting color changes.”

He completed the text using seven-year, cast vinyl for the lettering. However, for the G&L logo, Marshall implemented Signgold’s Florentine Swirl Gild — which he proudly reports is the first time it’s ever been used in Galway.

Marshall painted stripes and the panel with ivory 1Shot to highlight the pillars’ detailing. To enhance his handiwork’s lifespan, he gave the fascia a second coat of dark-blue paint. Due to cold December temperatures and moist, coastal air, the paint bubbled and required wet-abrasion and repainting. However, his perseverance paid off — the sign still “looks the business” a year later. SignGold

SPONSORED VIDEO

Introducing the Sign Industry Podcast

The Sign Industry Podcast is a platform for every sign person out there — from the old-timers who bent neon and hand-lettered boats to those venturing into new technologies — we want to get their stories out for everyone to hear. Come join us and listen to stories, learn tricks or techniques, and get insights of what’s to come. We are the world’s second oldest profession. The folks who started the world’s oldest profession needed a sign.

You may like

INX Promotes Three to Vice President

6 Sports Venue Signs Deserving a Standing Ovation

Hiring Practices and Roles for Women in Sign Companies

Subscribe

Bulletins

Get the most important news and business ideas from Signs of the Times magazine's news bulletin.

Most Popular

-

Tip Sheet4 days ago

Tip Sheet4 days agoAlways Brand Yourself and Wear Fewer Hats — Two of April’s Sign Tips

-

Business Management2 weeks ago

Business Management2 weeks agoWhen Should Sign Companies Hire Salespeople or Fire Customers?

-

Women in Signs2 weeks ago

Women in Signs2 weeks ago2024 Women in Signs Award Winners Excel in Diverse Roles

-

Real Deal5 days ago

Real Deal5 days agoA Woman Sign Company Owner Confronts a Sexist Wholesaler

-

Benchmarks1 day ago

Benchmarks1 day ago6 Sports Venue Signs Deserving a Standing Ovation

-

Editor's Note1 week ago

Editor's Note1 week agoWhy We Still Need the Women in Signs Award

-

Line Time2 weeks ago

Line Time2 weeks agoOne Less Thing to Do for Sign Customers

-

Product Buying + Technology1 week ago

Product Buying + Technology1 week agoADA Signs and More Uses for Engraving Machines