When businessmen rail against the evils of government, it’s easy to forget that many of America’s most profound technological breakthroughs in the past 75 years were spawned by public money, not private investments. In fact, the list of high-tech firms that owe their existence to government-financed research and development might be as large as your local telephone book. Although entrepreneurs certainly play key roles in bringing new technology to market, taxpayers are the unsung heroes of America’s high-tech boom.

The prohibitive cost of research currently forms a substantial roadblock for the optoelectronics industry, as it strives to compete in the market for lighting products. The Optoelectronics Industry Development Association is currently lobbying Congress to appropriate $250 million during the next five years to enable development of LED lighting. According to industry analysts, without a boost from Uncle Sam, LEDs will account for only 10% of the entire lighting market by 2025.

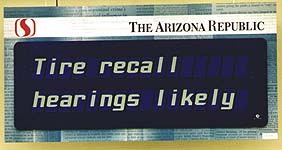

Because of these obstacles, recent marketing of LED channel letters and border tubes perhaps raised higher expectations than those warranted by the current state of the art. Although LEDs currently dominate the electronic-sign industry (Fig. 1), the crystal ball is far less clear regarding the future of electronic lighting.

Sticker shock

LEDs possess the brightness and efficiency to compete with conventional light sources. Initial costs, however, are still prohibitive for the majority of general lighting applications. Roland DGA Corporation Haitz, research and development manager of Agilent Technologies’ semiconductor product group, estimates that an LED lamp with light output equivalent to a standard 100-watt incandescent bulb would cost approximately $150 — far too expensive to be practical.

Because the U.S. market for conventional light bulbs is an estimated $3.5 billion, with a global market of $11.5 billion, the stakes are high. Although LEDs account for only a small percentage of today’s lighting market, this share is expected to triple within the next six years.

LEDs have found niche markets in special applications where higher initial cost is less of a concern to customers. For example, approximately 10% of all red traffic lights in the United States have already been converted from 150-watt conventional bulbs to 15-watt LED lights. Because LED traffic lights save substantial energy and offer 10-year lifetimes, state and local departments of transportation are taking advantage of the lower operating and maintenance costs.

To a lesser degree, this rationale impacts the signage market. For example, if a major hotel chain typically installs large channel letters 15-20 stories above the ground, maintenance cost is an important concern. In cases where signs are difficult and costly to service, absorbing the higher front-end cost of LED lighting might be justifiable. But at present, manufacturers of LED channel-letter lighting do not specify their products for large channel letters of this type.

Liberating light

To compete with conventional lamps, scientists and engineers must solve the riddle of how to glean more of the light emitted by an LED’s semiconductor chip. Additionally, effective ways must be found to create white light in proper tones for everyday use.

Currently, LEDs create white light in three different ways:

1) Mixing light beams from different colors of LEDs.

2) Coating the LED housing’s inside surface with phosphors, and using blue LED chips to excite this fluorescent coating (e.g. a fluorescent lamp); and

3) Photon-recycling. The Boston University Photonics Center recently developed a white-light LED that incorporates a layered-chip structure. By laminating an AlInGaP (aluminum, indium, gallium, phospho- rus) chip onto a blue-emitting, gallium nitride chip, white light is produced by the color mixture of re- cycled and directly emitted photons.

With current technology, only a small percentage of the photons emitted by an LED chip escape the diode as usable light. To improve lighting efficiency, research has focused on altering the conventional shape and structure of semiconductor chips.

LumiLeds Lighting (San Jose, CA) is a pioneer in this development, offering a new type of LED that incorporates a special chip formed into an inverted pyramid. This shape improves the LED’s optical-transmission properties, yielding efficiency as high as 50%. LumiLeds plans to produce the new LEDs commercially by the end of this year.

Because this technology applies strictly to AlInGaP diodes, however, only red and yellow LEDs can be produced. The task of getting similar efficiencies from gallium nitride (blue) diodes is a daunting problem that represents an important reason why the optoelectronics industry needs federal dollars. In the meantime, however, applications that use red or yellow diodes (including signs and decorative lighting) should benefit from improved efficiency.

E-ink headlines

In August, The Arizona Republic (Phoenix) became the world’s first newspaper to use electronic ink for presenting daily news (Fig. 2). The newspaper launched a three-month pilot program, placing E-ink’s (Cambridge, MA) Immedia

Tip Sheet1 week ago

Tip Sheet1 week ago

Photo Gallery3 days ago

Photo Gallery3 days ago

Ask Signs of the Times5 days ago

Ask Signs of the Times5 days ago

Real Deal2 weeks ago

Real Deal2 weeks ago

Benchmarks1 week ago

Benchmarks1 week ago

Photo Gallery5 hours ago

Photo Gallery5 hours ago

Women in Signs2 weeks ago

Women in Signs2 weeks ago

Women in Signs1 week ago

Women in Signs1 week ago